We present here an implementation of Ponte-Castaneda variational bound in non-linear elasticity [1]. It deals with the homogenization of a composite made of a matrix and spherical inclusions. The two phases have a non-linear elastic behaviour. The variational bound from Ponte-Castaneda is based on the computation of the strain second-moments.

This tutorial first recalls the scheme, and presents the implementation.

where \(N\) is the number of phases and \(\chi_r\) is characteristic function of phase \(r\).

The local potential \(w_r\) is a non-linear function of the strain \(\underline{\varepsilon}\), but here we focus on potentials of the form \[\begin{aligned} w_r(\underline{\varepsilon})={\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 9}{\displaystyle 2}} k_r\, \varepsilon_m^2+f_r (\varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}^2) \end{aligned}\] where \[\begin{aligned} \varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}= \sqrt{{\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 2}{\displaystyle 3}}\underline{\varepsilon}^d:\underline{\varepsilon}^d}\qquad\text{where}\quad \underline{\varepsilon}^d = \underline{\varepsilon}- {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 1}{\displaystyle 3}} \mathrm{tr}\left(\underline{\varepsilon}\right)\underline{1} \qquad\text{and}\quad \varepsilon_m={\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 1}{\displaystyle 3}} \mathrm{tr}\left(\underline{\varepsilon}\right) \end{aligned}\] In the variational approach, the homogenization problem is equivalent to a minimization problem: \[\begin{aligned} \underline{\varepsilon}=\underset{\underline{\varepsilon}\in\mathcal K(\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}})}{\textrm{argmin}} \langle w(\underline{\varepsilon})\rangle \end{aligned}\]where the space of kinematically admissible fields \(\mathcal K(\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}})\) is introduced depending on the boundary conditions used, and it makes intervene the loading \(\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}}\) (which will be our total strain \(\texttt{eto}\)). The \(\langle.\rangle\) denotes the average on the representative volume element.

where \(c_r\) is the volume fraction of phase \(r\) and \(W_0^{\mathrm{eff}}(\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}})\) is the effective energy relative to a ‘linear comparison composite’ which is heterogeneous, and whose elastic moduli are the \(k_r\) and the \(\mu_0^r\).

The stationarity conditions associated to the minimization on \(\mu_0^r\) are: \[\begin{aligned} {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle \partial W_0^{\mathrm{eff}}}{\displaystyle \partial \mu_0^r}} = c_r\,{\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle \partial f_r^*}{\displaystyle \partial \mu_0^r}} \end{aligned}\] which can be shown to be equivalent to \[\begin{aligned} \mu_0^r= {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 2}{\displaystyle 3}} {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle \partial f_r}{\displaystyle \partial e}}\left(\langle \varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}^2\rangle_r\right) \end{aligned}\] where \(\varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}\) is relative to \(\underline{\varepsilon}\) solution of the homogenization problem: \[\begin{aligned} \mathrm{div}\left(3k_r\,\varepsilon_m\,\underline{1}+2\mu_0^r\,\underline{\varepsilon}^d\right)=0,\qquad\underline{\varepsilon}\in\mathcal K(\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}}) \end{aligned}\] Besides, noting that \[\begin{aligned} W_0^{\mathrm{eff}}(\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}})=\sum_r c_r\,\left({\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 9}{\displaystyle 2}} k_r\,\langle\varepsilon_m^2\rangle_r+{\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 3}{\displaystyle 2}} \mu_0^r\langle \varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}^2\rangle_r\right) \end{aligned}\] it follows that \[\begin{aligned} \langle \varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}^2\rangle_r= {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 2}{\displaystyle 3c_r}}{\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle \partial W_0^{\mathrm{eff}}}{\displaystyle \partial \mu_0^r}} \end{aligned}\]The resolution hence consists in \[ \text{Find}\,e^r=\langle \varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}^2\rangle_r\,\text{such that}\quad\langle \varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}^2\rangle_r= {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 2}{\displaystyle 3c_r}}{\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle \partial W_0^{\mathrm{eff}}}{\displaystyle \partial \mu_0^r}} \] where \(W_0^{\mathrm{eff}}\) is the effective energy of a linear comparison composite whose elastic moduli are \(k_r\) annd \(\mu_0^r\) such that: \[ \mu_0^r= {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 2}{\displaystyle 3}}{\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle \partial f_r}{\displaystyle \partial e}}\left(\langle \varepsilon_{\mathrm{eq}}^2\rangle_r\right). \]

where \(\underline{\mathbf{C}}_0^{\mathrm{eff}}\) is the effective elasticity of the linear comparison composite. In our case, we use Hashin-Shtrikman bounds.

The tangent operator is given by \[\begin{aligned} \dfrac{\mathrm{d}\underline{\sigma}}{\mathrm{d}\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}}}=\underline{\mathbf{C}}_0^{\mathrm{eff}}+\dfrac{\mathrm{d}\underline{\mathbf{C}}_0^{\mathrm{eff}}}{\mathrm{d}\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}}} \end{aligned}\]Here, the derivative of \(\underline{\mathbf{C}}_0^{\mathrm{eff}}\) w.r.t. \(\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}}\) can be computed by derivating the Hashin-Shtrikman moduli w.r.t. the secant moduli \(\mu_0^r\) and the derivatives of these moduli w.r.t. \(\overline{\underline{\varepsilon}}\). However, it is tedious and in the implementation, we see that the convergence of the Newton Raphson algorithm is good if we only retain the first term \(\underline{\mathbf{C}}_0^{\mathrm{eff}}\) in the tangent operator.

where \(n\) is between \(0\) and \(1\), which means that \(f_r(e)=\dfrac{\sigma_r^0}{n+1}\,e^{\frac{n+1}2}\) (note that the function \(f_r\) is effectively concave relatively to \(e\), because \(0\lt n\leq 1\)).

Moreover, we make the choice of purely elastic inclusions. Hence, only the matrix is non-linear and has a secant modulus.

The unknowns of our non-linear problem are the \(e^r\). The secant moduli \(\mu_0^r\) can be computed by derivation of the function \(f_r\) which is given by the behaviour. In the precise case detailed above, we have \[\begin{aligned} {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle \partial f_r}{\displaystyle \partial e}}(e)=\dfrac{\sigma_r^0}{2}\,e^{\frac{n-1}2}\qquad\text{and}\quad\mu_0^r=\dfrac{\sigma_r^0}{3}\,\left(e^r\right)^{\frac{n-1}2} \end{aligned}\] Then, the effective energy of the linear comparison composite can be computed via a mean-field scheme. In our implementation, we proposed to use the Hashin-Shtrikman bound. The \(e^r\) must then cancel the following residue: \[\begin{aligned} r_{e^r}=e^r - {\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle 2}{\displaystyle 3\,c_r}}{\displaystyle \frac{\displaystyle \partial W_0^{\mathrm{eff}}}{\displaystyle \partial \mu_0^r}} \end{aligned}\]which means that we only need the derivative of the Hashin-Shtrikman

bound. This will be given by the

tfel::material::homogenization functionalities.

All the files are available here

For the jacobian, we adopt the Numerical Jacobian, which

means that the beginning of the mfront file reads:

@DSL ImplicitII;

@Behaviour PC_VB_92;

@Author Martin Antoine;

@Date 12 / 12 / 25;

@Description{"Ponte Castaneda second-order estimates for homogenization of non-linear elasticity (one potential), based on second-moments computation"};

@UseQt true;

@Algorithm NewtonRaphson_NumericalJacobian;

@PerturbationValueForNumericalJacobianComputation 1e-10;

@Epsilon 1e-12;Moreover, the following libraries will be needed for computation of the stress and secant modulus:

@TFELLibraries {"Material"};

@Includes{

#include "TFEL/Material/IsotropicModuli.hxx"

#include "TFEL/Material/HomogenizationSecondMoments.hxx"

#include "TFEL/Material/LinearHomogenizationBounds.hxx"

}We define two state variables which are the averages (on each phase) of the squares of the equivalent strains, and correspond to the \(e^r\):

@StateVariable real e_0;

e_0.setEntryName("MatrixSquaredEquivalentStrain");

@StateVariable real e_r;

e_r.setEntryName("InclusionSquaredEquivalentStrain");The secant moduli are computed by derivation of function \(f_r\), which is detailed above. Hence

@Integrator {

//secant modulus/////////////////////////////////

const auto po = std::pow(max(e_0+de_0,real(1e-10)),0.5*(n_-1));

const auto mu0 = sig0/3.*po;The second moment is given by the function

computeMeanSquaredEquivalentStrain (see documentation):

//second moments/////////////////////////////////

const auto em2 = tfel::math::trace(eto+deto)/3.;

const auto ed = tfel::math::deviator(eto+deto);

const auto eeq2 = 2./3.*(ed|ed);

using namespace tfel::material;

const auto kg0 = KGModuli<stress>(k_m,mu0);

const auto kgr = KGModuli<stress>(kar,mur);

using namespace tfel::material::homogenization::elasticity;

const auto eeq2_ = computeMeanSquaredEquivalentStrain(kg0,fr,kgr,em2,eeq2);

const auto eeq20=std::get<0>(eeq2_);

const auto eeq2r=std::get<1>(eeq2_);Now we can write the residues:

There is no jacobian because we use the

NumericalJacobian. The macroscopic stress is given by the

Hashin-Shtrikman lower bound (indeed, the lower bound is better suited

for soft matrix and rigid inclusions):

//sigma//////////////////////////////////////

vector<real> tab_f={1-fr,fr};

vector<stress> tab_k = {k_m,kar};

vector<stress> tab_mu = {mu0,mur};

const auto HSB=computeIsotropicHashinShtrikmanBounds<3,stress>(tab_f,tab_k,tab_mu);

const auto LB=std::get<0>(HSB);

const auto kHS=std::get<0>(LB);

const auto muHS=std::get<1>(LB);

Chom=3*kHS*J+2*muHS*K;

sig = Chom*(eto+deto);

}(Note that Chom is the effective elastic tensor, defined

here as a local variable). Afterwards, we can give the tangent

operator:

We then use MTest to simulate a strain-imposed test.

MTest file is the following:

@ModellingHypothesis 'Tridimensional';

@Behaviour<Generic> 'src/libBehaviour.so' 'PC_VB_92';

@ExternalStateVariable 'Temperature' {0 : 1000,1:1000};

@MaterialProperty<constant> 'sig0' 1.e9;

@MaterialProperty<constant> 'n_' 0.05;

@MaterialProperty<constant> 'k_m' 1.e9;

@MaterialProperty<constant> 'kar' 1.e15;

@MaterialProperty<constant> 'mur' 1.e15;

@MaterialProperty<constant> 'fr' 0.25;

@ImposedStrain 'EXX' {0 : 0, 100 : 0.8660254};

@ImposedStrain 'EYY' {0 : 0, 100 : -0.8660254};

@ImposedStrain 'EZZ' {0 : 0, 100 : 0};

@ImposedStrain 'EXY' {0 : 0, 100 : 0};

@ImposedStrain 'EXZ' {0 : 0, 100 : 0};

@ImposedStrain 'EYZ' {0 : 0, 100 : 0};

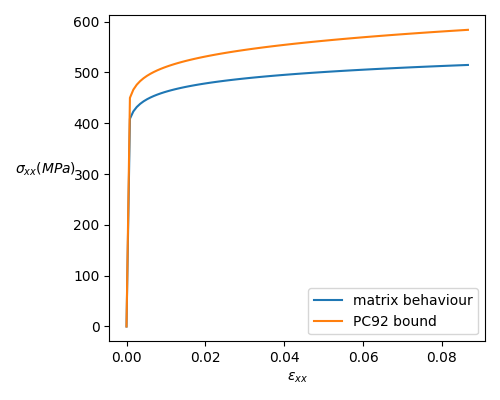

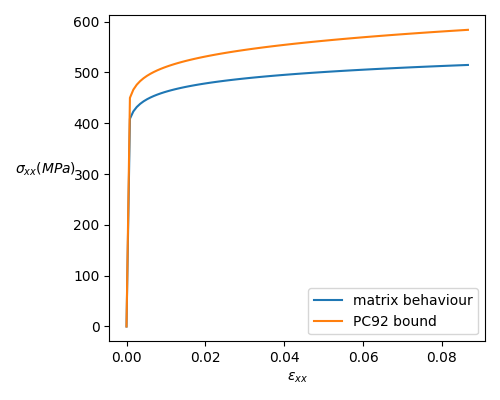

@Times {0.,10 in 100};The macroscopic stress \(\sigma_{xx}\) is represented below as a function of the macroscopic strain \(\varepsilon_{xx}\):

We also plotted the behaviour of the matrix when there is no inclusions (it gives an idea of the reinforcement given by the inclusions).